Female de-miners of Nagorno-Karabakh

Hello Eva, Could you tell me a little bit about yourself, what you currently do and your story so far?

Hi Jai, thanks for inviting me to share my work. I’m a writer and documentary photographer based in London. Growing up in Brighton I was surrounded by creative influences, so I guess that shaped my early interests. Having always alternated between photography and writing, I decided to do a Masters in Photojournalism & Documentary Photography at London College of Communication, which seemed the perfect way to combine both.

Since graduating I’ve worked as a visual arts journalist – interviewing photographers and artists for publications like Huck Magazine, Feature Shoot and British Journal of Photography – as well as a freelance writer and photographer.

Stumbling across some of your work, I was really intrigued by your Project “De-Miners”, Could you tell me about the project and what brought you to documenting the first female de-mining team?

After graduating from my degree, I went to Laos to teach English and it was the first time I heard that Laos is the most bombed country, per capita, on earth. According to estimates, 1/3 of the two million tons of ordnance dropped on Laos by the U.S. between 1964 and 1973 failed to detonate – and as many as 80 million bombs remain unexploded. It struck me that people are still suffering from the remnants of a war that ended half a century ago and I knew I wanted to do a project about it. So I did some research and discovered The HALO Trust, the world’s largest humanitarian mine clearance organisation.

At the time, I was back in the UK and going out to Laos again just wasn’t feasible, so I looked into other locations where HALO was operating and came across Nagorno-Karabakh in the South Caucasus.

I’m often drawn to stories that challenge stereotypes, so when I heard about the female de-mining team I immediately knew I wanted to focus on them, because the image we have in our minds of the person carrying out this dangerous work is almost always male.

The portraits of the women alongside the landscapes really evoke a sense of peacefulness and empowerment, I can only imagine that the process of de-mining is a lengthy one but one that is very rewarding. Did the women have any interesting stories to share with you while you were out with them?

Yes, I was really interested in that discord between the beauty of the landscape and the hidden danger that lurks beneath the soil. Though I didn’t get as much time as I wanted to speak with the women, there was a day when it snowed heavily and we were stuck at a base camp in the mountains. There was a fire going and loads of tea (typical Karabakh hospitality) and it was a great opportunity for me to talk to the women and take photos of them off the minefield.

I remember one woman named Lucine, whose uncle was killed by a landmine and she explained how that was her main motivation for becoming a de-miner. I thought that showed the sheer commitment these women have for wanting to make the land safer for current and future generations in their community – even if it does mean putting their own lives on the line.

Working in a field of uncertainty and on land that is still a disputed territory must have provided you with some challenges, physically, mentally and photographically. Could you describe some of them and how you worked around them?

I think preparation is key, so everything from researching the region’s history to preparing for all possible things that could go wrong before I went (though obviously there are some things you can't prepare for).

Before going anywhere for a project, I find getting in touch with journalists on the ground (or those who’ve worked in the region before) and asking them for advice and contacts is really useful. Being with HALO was obviously a huge advantage because I had someone to supervise me, translate and drive the long distances to and from the minefields.

Photographically, there were many challenges. It was my first time shooting with a medium-format camera and I hadn’t factored in that I’d have to wear a plastic safety visor while shooting on the minefield, so that was really tricky as it kept fogging up. Also, with only 12 exposures per roll you have to reload the film quite often, and anyone who’s used a Bronica before knows how cumbersome those cameras can be. Of course the minefield comes with its own challenges. The most important thing to know was where the separation between cleared and uncleared land was – and to stay on the cleared side!

Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognised as a part of Azerbaijan, however, the region is governed by the Armenian Republic of Artsakh. In September this year tensions escalated and more clashes between armed forces occurred with reported casualties. What was the atmosphere like in 2018, Was it relatively peaceful or eerie?

Although it was relatively peaceful when I visited in 2018, there was a tense atmosphere and it was made all the more eerier because of the fog that hangs over the place during winter. Shots were still regularly being fired over the border from both sides, but as the line of contact is miles out of town you could visit Stepanakert and have no idea of the fighting going on, apart from the presence of soldiers in the streets. I’m sure everyday reality is different and for the people who live there, war continues to impact their lives and remains a constant background threat (now unfortunately a reality).

What I liked about the project was that the images are shot in a 6x6 format. I think this format allows for consistency when framing both portraits and landscapes, what was your reason for picking this format ?

When studying photography at sixth form, I learnt everything on film cameras and developed my own prints by hand in the darkroom, which is probably why I’ll always have a special attachment to film. Many of my favourite photographers including Lee Miller, Saul Leiter and Bruce Davidson shot on film. Another photographer I really admire is Anastasia Taylor-Lind and her 6x6 photographs were a strong influence on my work visually. I think there’s something intimate about the square format that helps people connect with the subject.

Your website describes you as a writer and photographer. Does your writing tend to inform your photography or is it the other way round.

I'd say I'm more of a writer than a photographer. I think the two go hand in hand though; there are some things that are better communicated visually and others through writing, but used together words and images have a doubly powerful effect when it comes to storytelling. These days I rarely take my camera out for the sake of it, but when I do I always say I should do this more often.

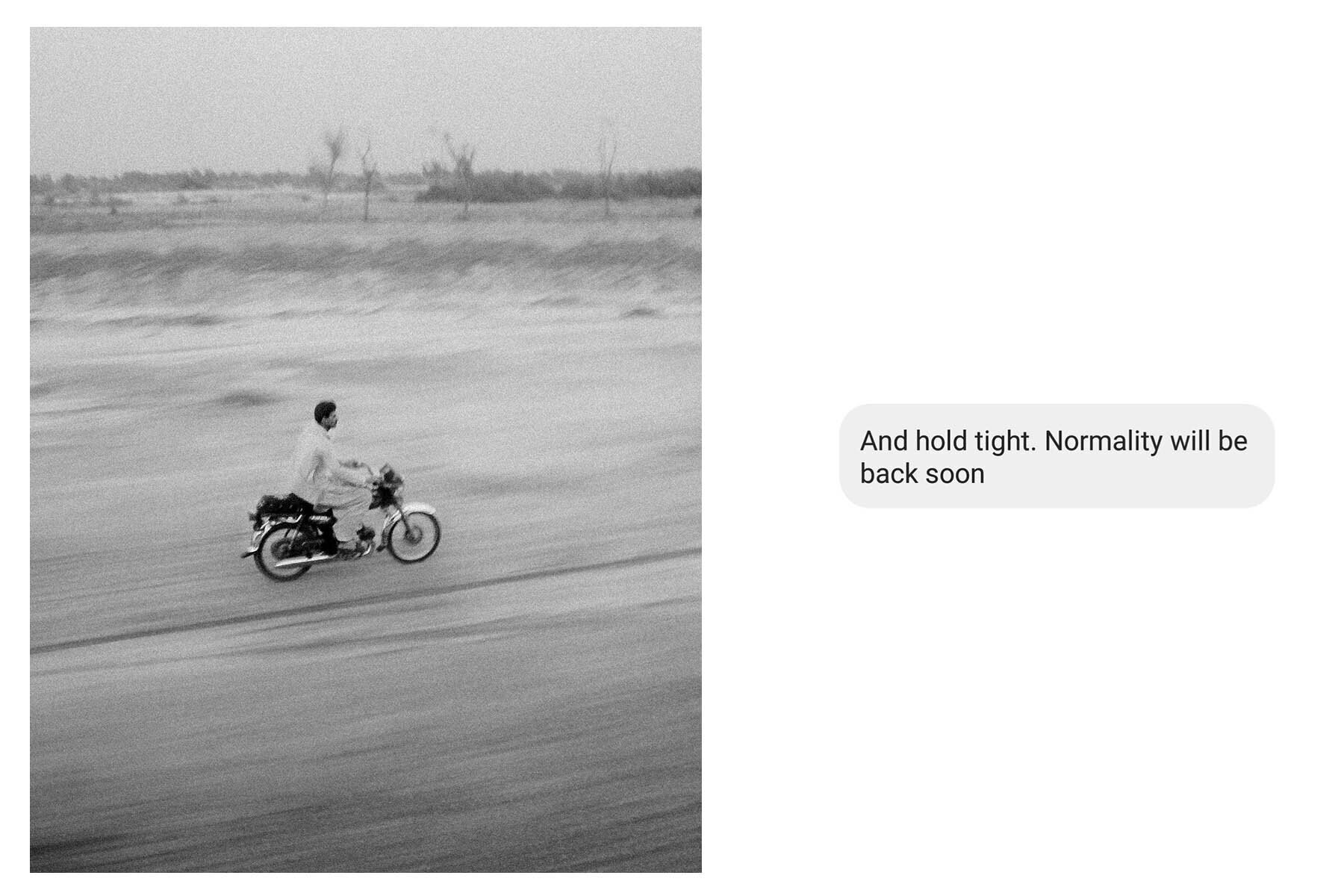

Another project you have curated is “Postcards from Quarantine”, These diptych works include a variety of powerful images sent in from artists around the world and are accompanied by a piece of text. How did this idea come to mind?

This project came about quite randomly actually. Just before the UK went into lockdown, I started taking screenshots of messages people were sending me with the idea of doing a project about the effects of isolation, but I had no idea how to visualise it. Then a friend in China messaged me with a photo of an orange tree he’d salvaged from a neighbour and I remember thinking it was a really beautiful image. That's how the idea came about to match the texts with lockdown images. Many of the texts I use describe experiences or feelings many of us will be able to relate to during this time, and I liked the idea of connecting strangers through the postcard format.

Initially I was just using material from friends and family, but now I have almost 300 submissions from around the world, so I’m really delighted that it’s had such a positive and wide-reaching response so far (thanks to Instagram).

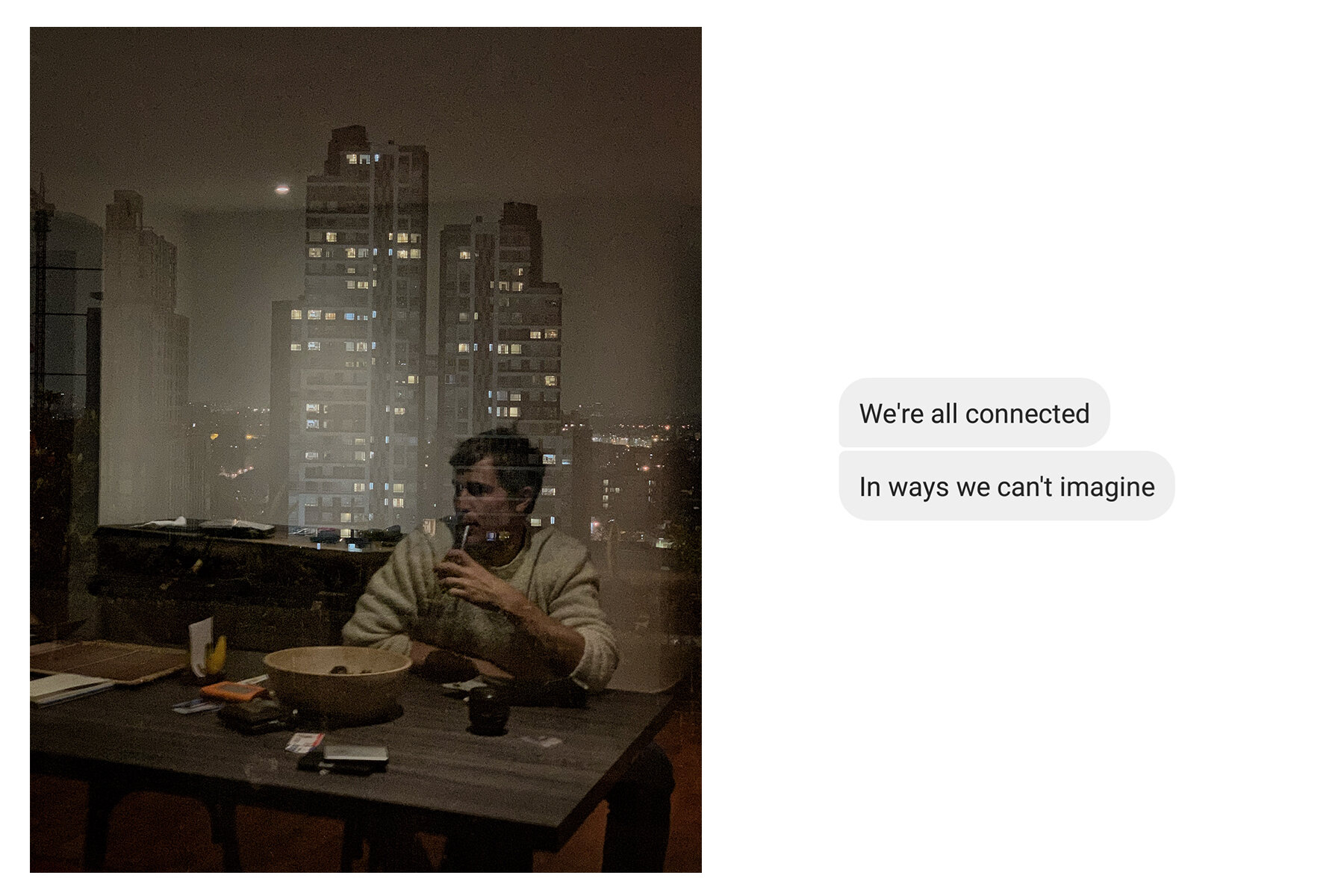

I love how the project is a work collaborative process between you and the artist. The pandemic and lengthy lockdowns have had a particularly big impact on people's mental health. Do you think a project like this helped occupy the minds of the creatives you worked with?

Definitely. Art can be so powerful in its capacity to heal and connect people and now it seems more important than ever (despite what the government says). I think it helps to know that we are all together in this, no matter where in the world you might be.

With many places going into a second lockdown, What are your plans for the Future? Are you looking to continue “Postcards from quarantine” and “De-Miners” or have you begun work on another journalistic project?

I’m still accepting submissions for my Postcards from Quarantine project, so anyone reading this is welcome to submit. All you need to do is send me an image you’ve taken during your lockdown and/or a message you’ve received (visit @postcards__from__quarantine for more details). I’m also currently working on ideas for new journalistic projects for 2021 – stay tuned!

Interview by Jai Toor